Uncategorized

Today is the first day of Fall.

My 3-year-old son and I went to the beach and ate hamburgers in the car.

Then crossed the railroad bridge to the saw grass and sand.

The air balanced gently between warm and cold. In the sunshine, the last of summer’s heat warms our skin like a loving farewell.

We dug soft sand and threw rocks and wandered as you only wander with a child.

Nothing to accomplish. No hurry.

A stream comes out of the forest, clear and cold as when it melted into a torrent a hundred miles away, up a mountain from here. Red and yellow leaves ride the stream to its end where sweet water joins salt. Salmon fingerlings pass through to the sea.

We lie on the sand watching dark blue waves and the patchwork sky of scudding clouds like massive billowed sails.

Hundreds of migrating crows come to drink from the stream and caper between sky and ground like flowing ink, written too fast to read.

They tease and flirt like teenagers in the park.

We play with toy cars, dwarfed beside the grey bones of a giant tree that drank sun for hundreds of years before it fell and drifted here; and Isaac repeats the question we all ask, waking to this world:

Why

Why

Why

Why

Why?

The truth will set you free. But not until it is finished with you.

– David Foster Wallace

Why facts don’t change minds

(Mostly not my writing, two interviews full of interesting evidence about our structural intransigence)

Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber are the authors of “The Enigma of Reason,” a new book from Harvard University Press. Their arguments about human reasoning have potentially profound implications for how we understand the ways human beings think and argue, and for the social sciences.

“Even after the evidence “for their beliefs has been totally refuted, people fail to make appropriate revisions in those beliefs,” the researchers noted. In this case, the failure was “particularly impressive,” since two data points would never have been enough information to generalize from…

If reason is designed to generate sound judgments, then it’s hard to conceive of a more serious design flaw than confirmation bias. Imagine, Mercier and Sperber suggest, a mouse that thinks the way we do. Such a mouse, “bent on confirming its belief that there are no cats around,” would soon be dinner. To the extent that confirmation bias leads people to dismiss evidence of new or underappreciated threats—the human equivalent of the cat around the corner—it’s a trait that should have been selected against. The fact that both we and it survive, Mercier and Sperber argue, proves that it must have some adaptive function, and that function, they maintain, is related to our “hyper-sociability.”

Mercier and Sperber prefer the term “myside bias.” Humans, they point out, aren’t randomly credulous. Presented with someone else’s argument, we’re quite adept at spotting the weaknesses. Almost invariably, the positions we’re blind about are our own…”

“…Stripped of a lot of what might be called cognitive-science-ese, Mercier and Sperber’s argument runs, more or less, as follows: Humans’ biggest advantage over other species is our ability to coöperate. Coöperation is difficult to establish and almost as difficult to sustain. For any individual, freeloading is always the best course of action. Reason developed not to enable us to solve abstract, logical problems or even to help us draw conclusions from unfamiliar data; rather, it developed to resolve the problems posed by living in collaborative groups.

“Reason is an adaptation to the hypersocial niche humans have evolved for themselves,” Mercier and Sperber write. Habits of mind that seem weird or goofy or just plain dumb from an “intellectualist” point of view prove shrewd when seen from a social “interactionist” perspective.

In a new book, “The Enigma of Reason” (Harvard), the cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber take a stab at answering this question. Mercier, who works at a French research institute in Lyon, and Sperber, now based at the Central European University, in Budapest, point out that reason is an evolved trait, like bipedalism or three-color vision. It emerged on the savannas of Africa, and has to be understood in that context.”

Elizabeth Kolbert – Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds – The New Yorker February 27, 2017, issue.

Henry Farrell: So, many people think of reasoning as a faculty for achieving better knowledge and making better decisions. You disagree. Why is the standard account of reasoning implausible?

HM: By and large, reasoning doesn’t fulfill this function very well. In many experiments — and countless real-life examples — reasoning does not drive people towards better knowledge or decisions. If people start out with the wrong intuitive idea, and then start reasoning, it rarely does them any good. They’re stuck on their initial wrong idea.

What makes reasoning fail is even more damning. Reasoning fails because it has a so-called ‘myside bias.’ This is what psychologists often call confirmation bias — that people mostly reason to find arguments that whatever they were already thinking is a good idea. Given this bias, it’s not surprising that people typically get stuck on their initial idea.

More or less everybody takes the existence of the myside bias for granted. Few readers will be surprised that it exists. And yet it should be deeply puzzling. Objectively, a reasoning mechanism that aims at sounder knowledge and better decisions should focus on reasons why we might be wrong and reasons why other options than our initial hunch might be correct. Such a mechanism should also critically evaluate whether the reasons supporting our initial hunch are strong. But reasoning does the opposite. It mostly looks for reasons that support our initial hunches and deems even weak, superficial reasons to be sufficient.

HF: So why did the capacity to reason evolve among human beings?

HM: We suggest that the capacity to reason evolved because it serves two main functions:

The first is to help people solve disagreements. Compared to other primates, humans cooperate a lot, and they evolved abilities to communicate in order to make cooperation more efficient. However, communication is a risky business: There’s always a risk that one might be lied to, manipulated or cheated. Hence, we carefully evaluate what people tell us. Indeed, we even tend to be overly cautious, rejecting messages that don’t fit well with our preconceptions.

Reasoning would have evolved in part to help us overcome these limitations and to make communication more powerful. Thanks to reasoning, we can try to convince others of things they would never have accepted purely on trust. And those who receive the arguments benefit by being given a much better way of deciding whether they should change their mind or not.

The second function is related but still distinct: It is to exchange justifications. Another consequence of human cooperativeness is that we care a lot about whether other people are competent and moral: We constantly evaluate others to see who would make the best cooperators. Unfortunately, evaluating others is tricky, since it can be very difficult to understand why people do the things they do. If you see your colleague George being rude with a waiter, do you infer that he’s generally rude, or that the waiter somehow deserved his treatment? In this situation, you have an interest in assessing George accurately and George has an interest in being seen positively. If George can’t explain his behavior, it will be very difficult for you to know how to interpret it, and you might be inclined to be uncharitable. But if George can give you a good reason to explain his rudeness, then you’re both better off: You judge him more accurately, and he maintains his reputation.

If we couldn’t attempt to justify our behavior to others and convince them when they disagree with us, our social lives would be immensely poorer and more complicated.

HF: So, if reasoning is mostly about finding arguments for whatever we were thinking in the first place, how can it be useful?

HM: Because this is only one aspect of reasoning: the production of reasons and arguments. Reasoning has another aspect, which comes into play when we evaluate other people’s arguments. When we do this, we are, on the whole, both objective and demanding. We are demanding in that we require the arguments to be strong before changing our minds — this makes obvious sense. But we are also objective: If we encounter a good argument that challenges our beliefs, we will take it into account. In most cases, we will change our mind — even if only by a little.

This might come as a surprise to those who have heard of phenomena like the “backfire effect,” under which people react to contrary arguments by becoming even more entrenched in their views. In fact, backfire effects seem to be extremely rare. In most cases, people change their minds — sometimes a little bit, sometimes completely — when exposed to challenging but strong arguments.

When we consider these two aspects of reasoning together, it is obvious why it is useful. Reasoning allows people who disagree to exchange arguments with each other, so they are in a better position to figure out who’s right. Thanks to reasoning, both those who offer arguments (and, hence, are more likely to get their message across) — and those who receive arguments (and, hence, are more likely to change their mind for the better) — stand to win. Without reasoning, disagreements would be immensely harder to resolve.

HF: Despite reason’s flaws, your book argues that it “in the right interactive context, works.” How can group interaction harness reason for beneficial ends?

HM: Reasoning should work best when a small number of people (fewer than six, say) who disagree about a particular point but share some overarching goal engage in discussion.

Group size matters for two reasons. Larger groups are less conducive to efficient argumentation because the normal back and forth of discussion breaks down when you have more than about five people talking together. You’ll see that at dinner parties: Four or five people can have a conversation, but larger groups either split into smaller ones, or end up in a succession of short “speeches.” On the other hand, smaller groups will necessarily encompass fewer ideas and points of view, lowering both the odds of disagreement and the richness of the discussion.

Disagreement is crucial because if people all agree and yet exchange arguments on a given topic, arguments supporting the consensus will pile up, and the group members are likely to become even more entrenched in their acceptation of the consensual view.

Finally, there has to be some commonality of interest among the group members. You’re not going to convince your fellow poker player to fold when she has a straight flush. However, it’s often relatively easy to find such a commonality of interest. For example, we all stand to gain from having more accurate beliefs.

This article is one in a series supported by the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Opening Governance that seeks to work collaboratively to increase our understanding of how to design more effective and legitimate democratic institutions using new technologies and new methods. Neither the MacArthur Foundation nor the Network is responsible for the article’s specific content. Other posts in the series can be found here.

Henry Farrell, washingtonpost.com © 1996-2020 The Washington Post

Nobody Understands (but they all think they do)

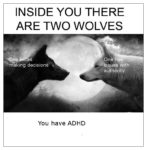

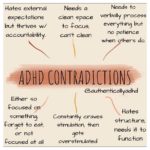

Executive Dysfunction, motivation, avoidance, resistance, disorganization

Memory: Short term, long term, working, and nonexistent

Time Blindness, distortion

Emotional Mess: Rejection sensitive dysphoria, anxiety, depression, guilt, shame, despair, etc.

Random leftovers

Part 1. There is no clean break between stories lived, dreamed, or told.

Our world is a measureless ocean of stories. Some are untouchable, uneditable, unmeeting parallels, distant in space/time. Some are sliding intimately through and around each other, mutually editing in motion.

We are stories who sprout further stories. Each of us is a tale partly told. We are suspenseful and unfinished. We are story-birds and every feather, large or small is someone or something else. Every chance meeting, ambition, fear, and plan is a story within our story. We are narrative fractals. Particles to self-observation, waves to outsiders. We all have public stories that we wear like expensive coats and secret stories in our silent flesh like pearls or tumors. Intimacy invites the listener or reader inside, then downward, past the public exhibits into the little-seen rooms and closer to the story you wouldn’t even know how to tell another person. Some are so private we don’t even grant ourselves clearance. Out of loyalty, pride or fear, some tales serve life sentences in solitary confinement, dying alone in the heart of the only witness.

To hear a story is to be offered a ride in it with an option to buy. Each telling generates new participants and versions. Stories are medicine, though whether they are magical elixir, placebo or poison is determined mostly by the state of the listener. To know something is to tell it to yourself, and hear it permanently.

The branching stories of our local neighborhoods mingle and tangle with those of our family, friends, loves, and enemies; familiar as those childhood streets until they fade in the gray distance of untold strangers.

Once upon a time…

Stories are the universal means to humanity’s ends. Stories are the acid test proof of humanity the species. They are the medium of culture, family, battle-plans, jokes, memes, and inventions. We could not conduct any of our signature business without them.

Therefore, to imagine a time of people before there were stories is sheer, well… fiction. No such animal existed. After our last common ancestor, there were wicked smart primates of many kinds, but the first people and the first stories are simultaneous, mutual creations, creating each other. The outside borders of humanity are where the stories cut off suddenly in the vacuum-like silence of animals*, plants and the great unknown. We exist in an atmosphere of exhaled and inhaled narrative. In the beginning…was the beginning.

The System:

Shared Narrative is the economy of human activity and stories are the coin. Underlying any economy is an agreement about how it works and the recognition of common units of exchange. A system of exchange must be understood well enough to be taken for granted.

In the narrative economy, I believe this means that the story elements used in a tale being told by A initiate a request inside the listener, B, to load their corresponding copy of that element in order to recognize meaning. We must each have our own copy of ABC or the alphabet wouldn’t work.

A narrative structure in the telling must match up with a corresponding structure in the listening. These elements must land, like drug or scent molecules, on matching neuroreceptors. If not, drugs would have no predictable common effect on us and we couldn’t say things like: “Is that cigarette smoke I smell?” We easily refer to the smell of fall leaves, wet dog, or shit because we can take the same recognition system for granted. Continue reading

THE NARCISSIST’S PRAYER:

That didn’t happen.

And if it did, it wasn’t that bad.

And if it was, that’s not a big deal.

And if it is, that’s not my fault.

And if it was, I didn’t mean it.

And if I did… You deserved it.

Marcus Tullius Cicero writing 2000 years ago on our hollowed-out foundations in the age of Trump.

- Laws are silent in time of war.

- The enemy is within the gates; it is with our own luxury, our own folly, our own criminality that we have to contend.

- Orators are most vehement when their cause is weak.

- When you have no basis for an argument, abuse the plaintiff.

- Nothing is more unreliable than the populace, nothing more obscure than human intentions, nothing more deceptive than the whole electoral system.

- It might be pardonable to refuse to defend some men, but to defend them negligently is nothing short of criminal.

- The false is nothing but an imitation of the true.

- The sinews of war are infinite money.

- It is the peculiar quality of a fool to perceive the faults of others and to forget his own.

- The higher we are placed, the more humbly we should walk.

- A liar is not believed even though he tells the truth.

I began meditating a few months back and it feels very positive, even transformative. That feeling is backed up empirically.

There are a number of interesting published studies on the effects of meditation but these two are amazing! Both have high strength of evidence. The titles below link to the full articles. Here’s the nutshell summary:

- Long term meditation alters brain anatomy in positive ways, such as larger hippocampal and frontal volumes of gray matter

- Meditation and yoga can rewrite our DNA and alter the gene expression of enduring trauma and stress correlates

(This series will be way better read from beginning to end, rather than end to beginning.)

Last time on Naked: Lizard boy began his quest to find love without fixing his broken heart first.

Because I didn’t know I needed to work, I didn’t do the work that needed to be done. And so I passed through the lives of many wonderful women: confusing, annoying and confounding them as I walked confidently in two different directions. Continue reading

“The Brain tunes itself to criticality, maximizing information processing”

Our brains are clearly amazing at processing the “blooming, buzzing1” world around us. A recent experiment supports the theory that when neurons work together they actively cooperate to achieve their maximum processing capacity. They seek the urgent, intense edge of their ability. Picture them as the human runners in an Amazon “fulfillment center” except happy in their work.

The entire brain appears to seek this set point or default working state at the maximum of its abilities: “Where it is as excitable as it can be, without tipping into disorder, similar to a phase transition.” A phase transition is where matter transitions from one state, liquid, solid, or gaseous, to a different state.

In other words, our brains are balanced about one millimeter from chaos and disorder. That’s all of us, all the time. Returning from sleep or other off duty moments the brain tunes and retunes itself seeking this point.

While the study neither reveals nor claims anything else about our neurology, I think it points a bright red arrow at possible organic causes of ADHD (as well as ASD, schizophrenia, etc). If the default human phenome, the standard, mass-produced person has this edge-of-chaos set-point, then genetic variation (known to be the prime cause of ADHD) could easily generate a different set point. This variation might generate the quirky, out of step processing that makes us so valuable in the modern workforce, wait, strike that…

It also seems logical that anything that alters this point results in behavioral instability.

More and other interesting details in the reports:

1 William James, writing about sensory processing. : “The baby, assailèd by eyes, ears, nose, skin, and entrails at once, feels it all as one great blooming, buzzing confusion; “