Part 1. There is no clean break between stories lived, dreamed, or told.

Our world is a measureless ocean of stories. Some are untouchable, uneditable, unmeeting parallels, distant in space/time. Some are sliding intimately through and around each other, mutually editing in motion.

We are stories who sprout further stories. Each of us is a tale partly told. We are suspenseful and unfinished. We are story-birds and every feather, large or small is someone or something else. Every chance meeting, ambition, fear, and plan is a story within our story. We are narrative fractals. Particles to self-observation, waves to outsiders. We all have public stories that we wear like expensive coats and secret stories in our silent flesh like pearls or tumors. Intimacy invites the listener or reader inside, then downward, past the public exhibits into the little-seen rooms and closer to the story you wouldn’t even know how to tell another person. Some are so private we don’t even grant ourselves clearance. Out of loyalty, pride or fear, some tales serve life sentences in solitary confinement, dying alone in the heart of the only witness.

To hear a story is to be offered a ride in it with an option to buy. Each telling generates new participants and versions. Stories are medicine, though whether they are magical elixir, placebo or poison is determined mostly by the state of the listener. To know something is to tell it to yourself, and hear it permanently.

The branching stories of our local neighborhoods mingle and tangle with those of our family, friends, loves, and enemies; familiar as those childhood streets until they fade in the gray distance of untold strangers.

Once upon a time…

Stories are the universal means to humanity’s ends. Stories are the acid test proof of humanity the species. They are the medium of culture, family, battle-plans, jokes, memes, and inventions. We could not conduct any of our signature business without them.

Therefore, to imagine a time of people before there were stories is sheer, well… fiction. No such animal existed. After our last common ancestor, there were wicked smart primates of many kinds, but the first people and the first stories are simultaneous, mutual creations, creating each other. The outside borders of humanity are where the stories cut off suddenly in the vacuum-like silence of animals*, plants and the great unknown. We exist in an atmosphere of exhaled and inhaled narrative. In the beginning…was the beginning.

The System:

Shared Narrative is the economy of human activity and stories are the coin. Underlying any economy is an agreement about how it works and the recognition of common units of exchange. A system of exchange must be understood well enough to be taken for granted.

In the narrative economy, I believe this means that the story elements used in a tale being told by A initiate a request inside the listener, B, to load their corresponding copy of that element in order to recognize meaning. We must each have our own copy of ABC or the alphabet wouldn’t work.

A narrative structure in the telling must match up with a corresponding structure in the listening. These elements must land, like drug or scent molecules, on matching neuroreceptors. If not, drugs would have no predictable common effect on us and we couldn’t say things like: “Is that cigarette smoke I smell?” We easily refer to the smell of fall leaves, wet dog, or shit because we can take the same recognition system for granted.

We arrive here equipped with common libraries of plots, characters, and symbols1. Then, there’s a place like a stage inside our minds where we “see” the stories that are told to us unpack themselves, unfold and unwind populating with the elements of our shared libraries. This is our system for perceiving the meaning of any narrative, including our own, the stories we tell ourselves. This system stages everything from jokes to fairy tales to history. It manages context, continuity, and meaning.

This evolutionary must-have makes us human. It is the underlying structure of interaction, it describes the path of world and self. It is also disturbingly possible that the limits of this system ARE the upper limits of human understanding and describing, perhaps we can tell no stories outside this structure.

The first part of this article made a case for the overwhelming importance of stories. Then I claimed the structural system of stories is hardwired. Below I make a casual case for these structures by leaning my full weight on the genius of others and using their ideas.

Part 2. Narrative DNA: Examples of Shared Libraries

- Plots (7 adaptable outlines)

- Characters (12 archetypes)

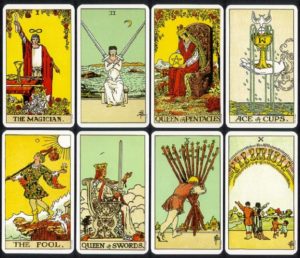

- Situations (78 tarot cards)

- Symbols: (thousands of meaningful props and touchstones)

The numbers of these examples are obviously not scientific facts, just ideas and examples coined by humans.

They are parts of a hypothesis from multiple sources.

This section and below is far from complete. I’m not about to describe the 78 situations shown in Tarot cards but you could absolutely spin a story from any layout of any combination of the cards (even absent any goal of psychic reading).  Each card HAS an independent meaning alone but the real meaning is the one shaped by its relationship to the cards around it. The Tarot cards are like the blocks of a visual programming language. The original distilling of these story elements in the very distant past and their endless popularity suggests they are part of an “alphabet” of narrative building blocks very much in use today.

Each card HAS an independent meaning alone but the real meaning is the one shaped by its relationship to the cards around it. The Tarot cards are like the blocks of a visual programming language. The original distilling of these story elements in the very distant past and their endless popularity suggests they are part of an “alphabet” of narrative building blocks very much in use today.

Tarot cards are not used by writers to concoct stories and most people don’t think of a tarot card when considering a situation. But Tarot cards show the way that these narrative ideas, connectors, and turning points can be easily codified into a situational alphabet. In recent years dozens of additional, completely original “tarot” decks have been created, adding to this resource.

Below, I’m plunking down an overview of archetypal characters and plots to add more support to my typically oversized claims. At the very bottom is a laughably small section on symbols.

Characters: Archetype Casting

Carl Jung defined 12 archetypes that symbolize basic human motivations that power our desires and goals. These archetypes resonate with us so much that it’s impossible to tell human stories without them. In fairy tales, they are presented in their pure essence, full strength. In realistic novels, they are shaved down, mixed, blended, then placed in a landscape of mundane events.

A complete list of archetypes cannot be made, nor can differences between archetypes be absolutely delineated.

Each comes with its own set of values, meanings and personality traits. Personalities are a mix of archetypal elements, however, one archetype tends to dominate. Does our understanding of archetypes come from ourselves? Does our understanding of ourselves come from them? The answer is Yes.

Here is an outline of the classic 12 archetypes:

1. The Innocent

The innocent archetype is judged sometimes for being naïve. They can be swept up in fantasy but they are also light-hearted optimists who can uplift others. The innocent looks for the good and the silver lining in every experience.

- Goal: to be happy

- Fear: being punished for doing something wrong

- Weakness: being too trusting of others

- Talent: faith and open-mindedness

2. The Orphan

Orphans are dependable, down to earth realists. Perhaps a little negative at times.

The orphan yearns to belong and may join many groups and communities to find a place where they fit in. Their heart has a Home shaped hole in it.

- Goal: to belong

- Fear: Not fitting in. Abandonment, being cast out and ostracized.

- Weakness: can be a little too cynical

- Talent: honest and open, pragmatic and realistic

3. The Hero

The hero is born to be strong and stand up for others. They often feel they have a destiny that they must accomplish. Heroes quest for justice and equality. They will stand up to even the most powerful forces if they think they are wrong.

- Goal: Helping others, protecting the weak

- Fear: being seen as weak or frightened

- Weakness: arrogance, always needing another battle to fight

- Talent: competence and courage

4. The Caregiver

Those who identify with the caregiver archetypes are full of empathy and compassion. Unfortunately, others can exploit their good nature for their own ends. Caregivers must pay attention to looking after themselves and learning to say no to others’ demands sometimes.

- Goal: to help others

- Fear: being considered selfish

- Weakness: being exploited by others and feeling put upon

- Talent: compassion and generosity

5. The Explorer

Explorers are never happy unless experiencing new things. This could be world travels or they may be happy learning about new ideas and philosophies. They find it hard to settle down at one job or relationship for long unless the job or relationship lets them retain their freedom to explore.

- Goal: to experience as much of life as possible in one lifetime

- Fear: getting trapped or being forced to conform

- Weakness: aimless wandering and inability to stick at things

- Talent: being true to their own desires and a sense of wonder

6. The Rebel

Rebels want to change whatever isn’t working in the world. They love change, but sometimes for its own sake. Rebels like to shake things up and stand a bit apart.

Sometimes rebels can abandon perfectly good traditions just because they have a desire for reform. Rebels can be charismatic and easily encourage others to follow them in their pursuit of rebellion.

- Goal: to overturn what isn’t working

- Fear: to be powerless

- Weakness: taking their rebellion too far and becoming obsessed by it

- Talent: having big, outrageous ideas and inspiring others to join them

7. The Lover

The lover seeks harmony in everything they do. They find it hard to deal with conflict and may find it difficult to stand up for their own ideas and beliefs in the face of more assertive types.

- Goal: being in a relationship with the people, work, and environment they love

- Fear: feeling unwanted or unloved

- Weakness: desire to please others at risk of losing own identity

- Talent: passion, appreciation, and diplomacy

8. The Creator

The creator is born to bring something into being that does not yet exist. They hate to be passive consumers of anything, much preferring to make their own entertainment. Creators are often artists or musicians though they can be found in almost any area of work.

- Goal: to create things of enduring value

- Fear: failing to create anything great

- Weakness: perfectionism and creative blocks caused by fear of not being exceptional

- Talent: creativity and imagination

9. The Jester

The jester livens up the party with humor and tricks, however, they have a deep soul. They want to make others happy and can often use humor to change people’s perceptions. Sometimes, however, the jester uses humor to cover his or her own pain.

- Goal: to lighten up the world and make others laugh

- Fear: being perceived as boring by others

- Weakness: frivolity, wasting time and hiding emotions beneath a humorous disguise

- Talent: seeing the funny side of everything and using humor for positive change

10. The Sage

The sage values ideas above all else. However, they can sometimes become frustrated at not being able to know everything about the world. Sages are good listeners and often have the ability to make complicated ideas easy for others to understand. They are often teachers.

- Goal: to use wisdom and intelligence to understand the world and teach others

- Fear: being ignorant, or being perceived as stupid

- Weakness: can be unable to make a decision as never believe they have enough information

- Talent: wisdom, intelligence and curiosity

11. The Magician

The magician is often very charismatic. They have a true belief in their ideas and desire to share them with others. They are often able to see things in a completely different way to other personality types and can use these perceptions to bring transformative ideas and philosophies to the world.

- Goal: To understand the fundamental laws of the universe

- Fear: unintended negative consequences

- Weakness: becoming manipulative or egotistical

- Talent: transforming people’s everyday experience of life by offering new ways of looking at things

12. The Ruler

The ruler loves to be in control. They often have a clear vision of what will work in a given situation. They believe they know what is best for a group or community and can get frustrated if others don’t share their vision. However, they usually have the interests of others at heart even if occasionally their actions are misguided.

- Goal: create a prosperous, successful family or community

- Fear: chaos, being undermined or overthrown

- Weakness: being authoritarian, unable to delegate

- Talent: responsibility, leadership

These archetypes dwell in a realm beyond the limits of a human lifespan, on an evolutionary timescale. Since they exist in all of us they seem to exist independently of us. Jung writes:

“They evidently live and function in the deeper layers of the unconscious, especially in that phylogenetic substratum which I have called the collective unconscious. This localization explains a good deal of their strangeness: they bring into our ephemeral consciousness an unknown psychic life belonging to a remote past. It is the mind of our unknown ancestors, their way of thinking and feeling, their way of experiencing life and the world, gods, and men. The existence of these archaic strata is presumably the source of man’s belief in reincarnations and in memories of “previous experiences”. Just as the human body is a museum, so to speak,  of its phylogenetic history, so too is the psyche.”

of its phylogenetic history, so too is the psyche.”

Jung described archetypes as imprints of momentous or frequently recurring situations in the lengthy human past. Jung understood them to be evolutionary structures which means their inclusion in our makeup is not figurative but factual. They are coded in our actual, not metaphorical, DNA.

I could describe the archetypes as super condensed epigenetic messages from our ancestors collected, reinforced and passed along to the next generation and the next and next; They are stars of our internal sky, the eternal background of dreams.

But this leaves me with a chicken vs egg problem. If the archetypes are essential structures for stories and humans wouldn’t be human without stories, how did those moving parts appear and hang together? They work as complete things, not partial things. Stories need archetypes to exist but why would archetypes exist in a world without stories? How would the system come online while incomplete?

Plots: 3, 7 or 20

English novelist E. M. Forster described plot as the cause-and-effect relationship between events in a story. According to Forster, “The king died, and then the queen died, is a story, while The king died, and then the queen died of grief, is a plot.”

The 3 Plots

William Foster Harris, in The Basic Patterns of Plot, suggests that there are three plot types: The happy ending, the unhappy ending, and tragedy.

The 7 Plots

Christopher Booker sees seven plots. The 7 story archetypes are:

- Overcoming the Monster.

- Rags to Riches.

- The Quest.

- Voyage and Return.

- Comedy.

- Tragedy.

- Rebirth.

The 20 Plots

Ronald Tobias, in his book, 20 Master Plots, and how to build them, describes 20 common story plots and gives lots of detail on how to construct complete stories around them. I see ways that these might be a bit redundant and further simplified but he’s trying to inspire writers, not reduce things to their least state. Apparently, these were summarized (as used here) by David Straker.

1. Quest

The hero searches for something, someone, or somewhere. In reality, they may be searching for themselves, with the outer journey mirrored internally. They may be joined by a companion, who takes care of minor detail and whose limitations contrast with the hero’s greater qualities.

2. Adventure

The protagonist goes on an adventure, much like a quest, but with less of a focus on the end goal or the personal development of the hero. In the adventure, there is more action for action’s sake.

3. Pursuit

In this plot, the focus is on chase, with one person chasing another (and perhaps with multiple and alternating chases). The pursued person may be often cornered and somehow escape so that the pursuit can continue. Depending on the story, the pursued person may be caught or may escape.

4. Rescue

In the rescue, somebody is captured, who must be released by the hero or heroic party. A triangle may form between the protagonist, the antagonist and the victim. There may be a grand duel between the protagonist and antagonist, after which the victim is freed.

5. Escape

In a kind of reversal of the rescue, a person must escape, perhaps with little help from others. In this, there may well be elements of capture and unjust imprisonment. There may also be a pursuit after the escape.

6. Revenge

In the revenge plot, a wronged person seeks retribution against the person or organization which has betrayed or otherwise harmed them or loved ones, physically or emotionally. This plot depends on moral outrage for gaining sympathy from the audience.

7. The Riddle

The riddle plot entertains the audience and challenges them to find the solution before the hero, who steadily and carefully uncovers clues and hence the final solution. The story may also be spiced up with terrible consequences if the riddle is not solved in time.

8. Rivalry

In rivalry, two people or groups are set as competitors that may be good-hearted or as bitter enemies. Rivals often face a zero-sum game, in which there can only be one winner, for example where they compete for a scarce resource or the heart of another person.

9. Underdog

The underdog plot is similar to rivalry, but where one person (usually the hero) has less advantage and might normally be expected to lose. The underdog usually wins through greater tenacity and determination (and perhaps with the help of friendly others).

10. Temptation

In the temptation plot, a person is tempted by something that, if taken, would somehow diminish them, often morally. Their battle is thus internal, fighting against their inner voices which tell them to succumb.

11. Metamorphosis

In this fantastic plot, the protagonist is physically transformed, perhaps into a beast or perhaps into some spiritual or alien form. The story may then continue with the changed person struggling to be released or to use their new form for some particular purpose. Eventually, the hero is released, perhaps through some great act of love.

12. Transformation

The transformation plot leads to the changing of a person in some way, often driven by unexpected circumstances or events. After setbacks, the person learns and usually becomes something better.

13. Maturation

A maturation plot is a special form of transformation, in which a person grows up. The veils of younger times are lost as they learn and grow. Thus the rudderless youth finds meaning or perhaps an older person re-finds their purpose.

14. Love

The love story is a perennial tale of lovers finding one another, perhaps through a background of danger and woe. Along the way, they become separated in some way but eventually come together in a final joyous reunion.

15. Forbidden Love

The story of forbidden love happens when lovers are breaking some social rules, such as in an adulterous relationship or worse. The story may thus turn around their inner conflicts and the effects of others discovering their tryst.

16. Sacrifice

In sacrifice, the nobler elements of the human spirit are extolled as someone gives much more than most people would give. The person may not start with the intent of personal sacrifice and may thus be an unintentional hero, thus emphasizing the heroic nature of the choice and act.

17. Discovery

The discovery plot is strongly focused on the character of the hero who discovers something great or terrible and hence must make a difficult choice. The importance of the discovery might not be known at first and the process of revelation be important to the story.

18. Wretched Excess

In stories of wretched excess, the protagonist goes beyond normally accepted behavior as the world looks on, horrified, perhaps in the realization that ‘there before the grace of God go I’ and that the veneer of civilization is indeed thin.

19. Ascension

In the ascension plot, the protagonist starts in the virtual gutter, as a sinner of some kind. The plot then shows their ascension to becoming a better person, often in response to stress that would defeat a normal person. Thus they achieve deserved heroic status.

20. Descension

In the opposite to ascension, a person of initially high standing descends to the gutter and moral turpitude, perhaps sympathetically as they are unable to handle stress and perhaps just giving in to baser vices.

The Library of Symbols: Props, Settings, Signs, Directions

All I’m putting here is this large, colorful, and helpful graphic of some commonly shared symbols. I have more to say about them but that has to wait for now.

-* Animals are certainly not silent at all. Especially very smart animals seem to us, to be like us, to have and to be stories. The memories of animals; of mother, of danger, of our relationship and so on, are very like stories but lack the telling and crucially the need for telling. Animal memories inform their actions but do not lay the foundation for complex structures and a shared economy of knowledge. Animals are so intimately parts of our lives and stories that we unconsciously include them as equals. None of this means they are less than us, their life script simply doesn’t include this trait.

-1 We all get the same libraries but of course, the details of stories come out dyed the colors of our cultures.